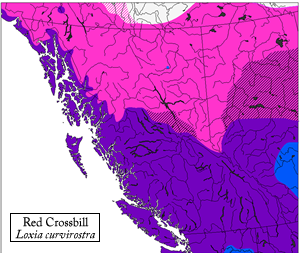

The taxonomy of the Red Crossbill ‘complex’ has been the topic of much discussion over the past 15+ years. Previous ornithologists attempted to grapple with the pronounced variation in size and bill structure in this species through the recognition of at least 8 different subspecies, but recent researchers studying this species have found its taxonomy to be far more complicated than what is represented by these somewhat arbitrarily-defined subspecies. In particular, Jeff Groth of the American Museum of Natural History published research in the early 1990s that showed the ‘Red Crossbill’ to consist of at least 8 discrete types (6 in B.C.) based on subtle differences in bill morphology and call notes. In many cases, these ‘call types’ broadly overlapped in distribution but rarely, if ever, interbred. They appeared to flock and mate based on call note, and recordings of their call notes could be used to differentiate among them (these differences are also often apparent to the human ear). These small differences, particularly those in bill structure, have evolved so that each ‘call type’ is able to exploit the seeds of a particular type of conifer, whether it be the small, soft seeds of hemlocks (small-billed types) or the large, hard seeds of pines (large-billed types). The situation appeared to suggest that the ‘Red Crossbill’ is actually a species complex involving multiple species with very similar plumage patterns and small (but apparently significant) differences in call notes and bill shape.

Other researchers over the past decade have followed up on this research and have found an additional call type (Type 9) in southern Idaho that was recently (March 2009) described as a completely new species, the ‘South Hills Crossbill’ (Loxia sinesciurus). It occurs alongside at least two other call types, but interbreeding between it and the other types occurs at a frequency of <1% of mated pairs. This assortative mating has led to a relatively high level of genetic divergence, and thus the description as a new species. A similar situation has occurred in Europe, which has led to the recognition of the Scottish Crossbill (Loxia scotica) and may lead to the recognition of additional species in the future.

Because of these recent advances, and the apparent dissolution of the previously-recognized subspecies, there is no currently-accepted system of intraspecific taxonomy within this species. The recognition of the ‘call type’ system, as outlined by Groth, has gained momentum over the past few years, however, and appears to be the dominant working taxonomy by ornithologists studying the species. As a result, this taxonomy will be followed for B.C., although the former subspecies that relate to the new ‘call types’ will be mentioned for historical context. In all likelihood, these call types represent distinct species.

The ‘call types’ recorded in British Columbia are as follows:

Type 1 (‘Spruce Crossbill’)

This call type corresponds with birds that were formerly classified as L.c.neogaea. It has been recorded in the Appalachian Mountains of eastern North America, as well as in southern B.C. and northwestern Washington, but likely also occurs along the southern border of the boreal forest in the intervening areas. It is one of the smallest and smallest-billed call types (only Type 3 is smaller). Its flight call is very similar to that given by Type 2, but averages slightly shorter, sharper, and dryer, without the descending quality to each note: chewt-chewt-chewt or kiip-kiip-kiip-kiip. It is also very similar to the calls of Types 3 and 5, and definitive identification of this call type may require the analysis of recordings and spectrographs. Type 1 birds in the Pacific Northwest have been found feeding on hemlock and Sitka Spruce, while birds in the Appalachians tend to focus on Eastern White Pine and White Spruce. White Spruce is abundant throughout the boreal forests of northern North America (including northern B.C.), and thus this call type may yet be found to be more widespread than the relatively few records indicate.

Type 2 (‘Ponderosa Pine Crossbill’)

This call type corresponds with birds formerly recognized as several different subspecies, including L.c.bendirei in B.C. This call type has been found widely throughout western North America, north to south-central B.C., as well as in various locations throughout the eastern United States and eastern Canada (especially in the Appalachians), and may occur throughout the intervening areas of central Canada. Type 2 may be the most widespread call type in North America. It is a relatively large, large-billed call type (only Type 6, which occurs in Mexico and southeastern Arizona, is larger). Its flight call is extremely similar to that of Type 1 birds, but averages slightly longer and more musical, with a distinctive descending quality to each note: cheewp-cheewp-cheewp-cheewp or kewp-kewp-kewp-kewp; sound recordings and spectrograph analysis are likely required for definitive identification. Type 2 birds are closely tied to ‘hard’ pines such as Lodgepole Pine and, especially, Ponderosa Pine, but will occasionally forage on the seeds of spruces and Douglas-fir and it may have the most varied diet of any of the call types.

Type 3 (‘Hemlock Crossbill’)

This call type includes birds that were formerly recognized as L.c.sitkensis. It has been found primarily along the Pacific coast of Canada and the United States (north to Alaska), as well as in the northeastern U.S. and eastern Canada (possibly also occurring in intervening areas of central Canada). This is the smallest and smallest-billed call type, and the males have a greater tendency to have extensively yellow or orange plumage than in other types. Its flight calls are weaker and squeakier than the flight calls of other call types, with a descending quality to each note: chep-chep-chep-chep or kyip-kyip-kyip-kyip. It is very closely associated with hemlocks (Western and Mountain Hemlocks in B.C.) and appears to feed on other conifers (spruce, larch, Douglas-fir) only during periods of poor seed production in hemlock stands.

Type 4 (‘Douglas-fir Crossbill’)

This call type includes birds that were previously attributed to L.c.neogaea. It has been found throughout much of western North America, north at least to the Queen Charlotte Islands and east to the Rocky Mountains, as well as sporadically in the northeastern United States and eastern Canada. It is almost identical to Type 1 in size and structure, but has distinctive musical, bouncy flight call with an upslurred quality to each note that is audibly different from any other call type: kwit-kwit-kwit-kwit or whit-whit-whit-whit (the whit sound is very similar to the call notes of some Empidonax flycatchers, particularly Least and Dusky Flycatchers). It is closely associated with Douglas-fir in the west, and is especially common in areas where the coastal variety of this tree species occurs (interior forms of this tree do not retain their seeds in the cones throughout the winter, thus these crossbills do not have a food resource of sufficient size and reliability to support a large population); it will also consume the seeds of Lodgepole Pine, although this is not the preferred food source.

Type 5 (‘Lodgepole Pine Crossbill’)

This call type includes some birds that were previously assigned to L.c.bendirei. It has been found primarily in the Rocky Mountains and in mountain ranges west to California and north into the southern and central interior of British Columbia. It is a mid-sized call type, averaging slightly larger and larger-billed than Type 4 and Type 7, but slightly smaller and smaller-billed than Type 2. The call is very similar to that of Type 3, but is higher-pitched and slightly drier: chit-chit-chit-chit. It is closely associated with the interior race of Lodgepole Pine as well as with high-elevation forests of Engelmann Spruce, although it occasionally feeds on other conifers.

Type 7 (‘Cordilleran Crossbill’)

This call type does not correspond with any previously-described subspecies of Red Crossbill. It has been found sporadically in the mountains of western North America from the Cascades east to the Rocky Mountains, north into south-central British Columbia. It is a mid-sized type that averages slightly smaller than Types 2 and 5, but slightly larger than Types 1 and 4. Its flight calls are similar to those of Type 3 but are slightly flatter (lacking a descending quality to each note), stronger, and lower-pitched and sound somewhat warbled: chip-chip-chip-chip. Like Type 5, it is associated with interior race of Lodgepole Pine as well as Engelmann Spruce, but likely feeds on other conifers as well when necessary.

Source: Adkisson (1996); Groth (1996); Sibley (2000); Benkman (2007); Young (2008); Benkman et al. (2009)

|